WENATCHEE,

WASHINGTON

NOVEMBER 6, 1998

I got home today.

I can’t believe, as I read the previous pages I’ve written, how dense I

was. I missed all the foretelling incidents and I had no idea of the horror

that was about to happen to Central America in the form of Hurricane Mitch.

Sure, I saw reports of a hurricane forming out in the Caribbean. I never

connected it with the heavy rains in Bluefields that ruined the craft fair

there, but that was just the fringe of the storm and the forecast was that the

hurricane was going to turn and go north, turning up the eastern coast of

Honduras and maybe hit Mexico. Bluefields was lucky only to receive a

drenching. I just hoped that the hurricane would blow itself out at sea before

I was to fly home on October 31st.

Early in the week of October 25th the radio station reported that a man made

his way across swollen streams and fields of mud, he said, in the northern part

of Nicaragua, trying to reach a small town. He said they had no transportation

and no communication and there was so much water and rain where he came from

that there were five families of campesinos (farm workers) who had had no food

for five days..

It was reported as an isolated incident.

The weather report said Hurricane Mitch was going to hit the Yucatan

Peninsula. No one in Nicaragua was alarmed.

The next report was that Hurricane Mitch was stationary over Honduras, and

Nicaragua would get a lot of rain, particularly in the León-Chinandega area.

We’d been having rain every day for so long I think we all mostly just

shrugged. People in little mountain towns were asking for water to drink and

food and plastic, please, rolls of black plastic to keep the rain off. It was

duly reported and fairly well forgotten, I think.

Wednesday the wind and the rain hit. The houses in Nicaragua – the ones

I’ve been in, anyway – don’t have ceilings, the ceiling and the roof being one

and the same thing. The area between the top of the wall and the roof is

usually pretty well open so air can move through the house. There are often

openwork decorative concrete blocks in a row near the top of the wall, or set in

blocks to give the effect of a window, but also for air circulation in that hot

climate.

I was staying at Danelia’s house then. Her house has a clay tile roof and

it has leaks. The roof is high and steep and large, so she can’t afford to

repair it.

With the wind blowing hard when I went to bed Wednesday night I could feel

fine, mist-like spray on me. I didn’t say anything because everyone fusses so

about me, and it wasn’t cold. My bed was a cot on one side of a room, where Danelia and Lucia shared a bed on the other side. I slept a bit, then woke to

see Lucia had moved to the foot of the bed, curled up in a corner at the foot,

and Danelia had her colcha wrapped around her and was sitting huddled at the

foot, trying to avoid the leaks that hadn’t been there before. The fine mists

over me had turned into big drops that hit me in the face. I said nothing,

turned and must have gone back to sleep because soon I was awakened by Danelia

shaking my shoulder. “Elenita, todo está agua aquí.” (Everything’s water

here.) There was at least an inch of water on the floor, my blanket was

soaking wet but it wasn’t cold, and water was dripping everywhere while the wind

screamed and whipped overhead.

We went to a small room at the back of the house that has a corrugated metal

roof where the whole family was gathered, sitting on chairs, trying to stay out

from under water leaks.

They must have thought I was a real dumbhead, but I was trying hard not to

be any trouble to them, and there was nothing I could do but stay out of the way

and try not to be a problem.

The wind was whipping rain in sideways through the house and underneath the

clay roofing tiles. The street in front of the house was running like a river.

We were soaked through and stayed wet for the next four days. All our clothing

was wet.

For a while the electricity was off and we didn’t have running water for a

couple of days. When it came back on it was dirty so they caught rain water

and boiled that for cooking and drinking.

Little by little came reports on radio and television of things happening around

the country, but still no one had any idea of the horrors they would be hearing

later. Roads were washed out all over, and there was no way for people to

get to the smaller towns that were out in the country until the wind calmed down

so helicopters could go take a look.

What they saw then horrified them. Whole towns washed away with survivors

gathered on some high spot, with no water to drink, no food or shelter. Many

had lost family members. Where the land happened to be flat, there would be

standing water and mud engulfing things, but often the water rushed through with

unbelievable speed and strength and swept away everything in its path.

León, where I was, is a rather large city. It’s not flat but it isn’t what

you’d call hilly, it just has a slope to its streets. I’d ask people where

all that rain water was going that I’d see running down the street every day.

To the river? Well, not to a river, really, but one of the little gullies

that crosses the town. I’d only ever seen a little bit of water

flowing in them even after heavy rains. Not a river at all, really.

Thursday the gully that went through León was a killer. The water that came

running down the streets of town from the rains, the water that boiling down out

of the hills at breakneck speed, gathered in the gully that had a little park on

its flat bottom with a concrete basketball court, swings and a kids’ playground.

Thursday the gully that went through León was a killer. The water that came

running down the streets of town from the rains, the water that boiling down out

of the hills at breakneck speed, gathered in the gully that had a little park on

its flat bottom with a concrete basketball court, swings and a kids’ playground.

The water filled the gully and overflowed the top, taking off the backs of

houses and stores that lined the streets more than 50 feet above it. It carried

huge rooted stumps of mahogany trees that smashed buildings and ended against a

house wall as the water passed by. It smashed at least two bridges in the town

that I saw, tore up the concrete basketball pad and piled it on top of branches

and vegetation that it had ripped down to the mud. It killed people.

Latin American television and newspapers are somewhat more grisly than we

are accustomed to. There were pictures, after the water had subsided, of a ball

of brush left behind with a little girl’s legs sticking out among the branches.

A toddler’s right forearm and part of his left buttock protruding through a mud

slurry. The body of a man half buried face down in mud. A little boy’s nude

body found just as a pig heads out to eat it and is chased away. There were

lots of such images, of adults, too; I wish I could get them out of my mind.

On the morning television the camera went from one big ball of vegetation to

the next, twigs and leaves and branches that had gathered into a big ball as it

rolled down, picking up bodies on the way, as the stream cut through wherever

the water found its way. As the camera went from one ball to another, we could

see legs sticking out, the body enclosed in the center of the vegetation. The

commentator went from one ball to another, saying quietly, “Es nina.” (This is a

girl.) “Es nino.” (This is a boy.) “Es nina.” “Es nina.” “Es nino.” Adults

got caught too.

It was sickening.

When Danelia and I went down to see the washed-out bridge down by the

hospital on Sunday, two days later, that raging river was just a little stream

that I could once again step across without jumping. It was hard to look up and

believe that little stream, the Rio Chiquito, the Little River, could have

possibly been that monstrous wall of water way up there, leaving behind those

big destructive stumps, tearing out those houses up on the street above it.

But the horrors were not over. On Sunday at midnight there was a mudslide

on Cerro Casita that buried hundreds, maybe 2000 people, without warning. The

ground was soaked from weeks of heavy rains and the crater of the old volcano

had filled with water so it was a lake that soaked the earth from the insides of

the volcano. The earth let go in the night without warning and a two-mile-wide

mudslide swept down over the little villages and covered the houses. The next

day people were trying to dig them out while the mud avalanches would still

break through and the rescuers would have to flee for their lives. Men reported

hearing the screams of the victims trapped in their houses under the mud. Posoltega was the town lost.

Every day new horrors surfaced. As the weather cleared so helicopters could

get out into the remote areas, they found more and more desperate villagers

without homes, food or potable water. The army flew along the Coco River in the

north and found devastation there they hadn’t suspected. A family of five were

picked out of a tree where they’d been hanging on for three days, trying to stay

above the water below them, but they’d lost one child who was too weak and had

let go in the night. People who have no way to communicate have no way to tell

their story, and the mud-covered towns they kept finding were a surprise. It

was hard to get beyond the closer tragedies they couldn’t do anything about yet,

without looking for more people they couldn’t help either.

The infrastructure was down. The day I was supposed to go to Managua to the

airport to go home, Saturday, October 31, there were ten bridges under water

between León and Managua. When the water went down, there were bridges down,

too. Sometimes it was the center section of the bridge gone, sometimes it was

the bridge approaches that were gone. There was no way to get food and supplies

up to the people who needed it. The army started working to grade by-passes and

put in those metal emergency bridges so traffic could get by.

On Monday I was told that it was possible to get to Managua. You would

drive 10 kilometers to the first washed-out bridge and you would cross the river

hanging onto a rope, get on a truck on the other side and go to the next

washed-out bridge, cross the river hanging onto a rope again, get on a horse and

continue to the next bridge.

On Tuesday the following week, Danelia’s daughter Jasmina and friends tried

to return to Managua to go to university. They got past the first two bridges

that had been replaced with temporaries, but after that it was too long a walk

so they came back to León. By Thursday, November 5th, when I was supposed to go

to the airport again, there were temporary bridges in place for one-way traffic.

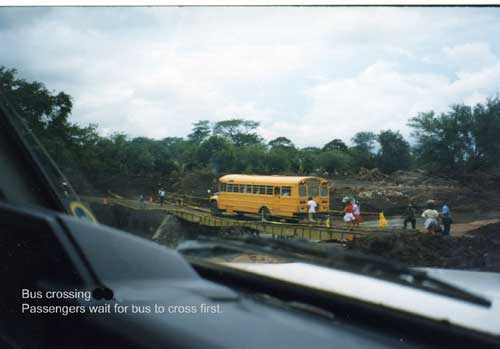

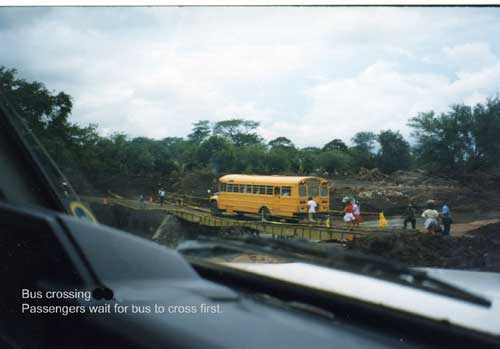

We crossed six of them on our way down. It was like road construction

anywhere: you sat and waited while a long line of cars and mostly trucks slowly

passed over the bridge, guided by a man giving hand signals so you didn’t run

off the tracks. There were buses of people who got off and walked across the

bridge to the other side so the bus could go across unloaded, then the people

got back in on the other side. I was pleased to see the large number of trucks

heading north with supplies: bottles of drinking water, rolls of plastic so

people could get out of the rain, food.

We crossed six of them on our way down. It was like road construction

anywhere: you sat and waited while a long line of cars and mostly trucks slowly

passed over the bridge, guided by a man giving hand signals so you didn’t run

off the tracks. There were buses of people who got off and walked across the

bridge to the other side so the bus could go across unloaded, then the people

got back in on the other side. I was pleased to see the large number of trucks

heading north with supplies: bottles of drinking water, rolls of plastic so

people could get out of the rain, food.

We passed flooded fields with crops still lying on their side, areas that

were flat and the water couldn’t run off like small lakes of mud, and

occasionally the smelly bloated body of a drowned cow. As we got closer to

Managua there was less and less sign of flooding and damage, even though I know

they had serious flooding in some sections.

I got home Friday, November 6. I hated to leave, but there was nothing I

could do to help. I wish I were a nurse and useful.

I expect that whole area to have rough time ahead. The flooded latrines

spreading raw sewage everywhere will have contaminated everything the water

spread to; nothing will be safe. The thousands of missing people will surface,

some of them alive. I hope there will be lots of nurses and doctors who can go

to those outlying villages and give medicines and injections to those people. I

can’t see medicine doing much good without professionals to administer it. They

need inoculations and fast, along with clean water. And let’s pray for decent flying weather so the helicopters can get food and

water out there where it’s needed.

This is a condensed version of the story I know. Every day there seemed to

be another horror revealed, another unbelievable disclosure.

On Monday night Cerro Negro, their biggest volcano, laid out a mile or so of

fresh lava. There was a picture of it on the front page of El Nueve Diario with

the caption, Por Que, Dios Mio? (Why, My God?)

They don’t need anything more to happen.

Chau, Elaine

Next

Back to 1998 letters.

Back Lolli's homepage

Back Lolli's homepage

Thursday the gully that went through León was a killer. The water that came

running down the streets of town from the rains, the water that boiling down out

of the hills at breakneck speed, gathered in the gully that had a little park on

its flat bottom with a concrete basketball court, swings and a kids’ playground.

Thursday the gully that went through León was a killer. The water that came

running down the streets of town from the rains, the water that boiling down out

of the hills at breakneck speed, gathered in the gully that had a little park on

its flat bottom with a concrete basketball court, swings and a kids’ playground.

We crossed six of them on our way down. It was like road construction

anywhere: you sat and waited while a long line of cars and mostly trucks slowly

passed over the bridge, guided by a man giving hand signals so you didn’t run

off the tracks. There were buses of people who got off and walked across the

bridge to the other side so the bus could go across unloaded, then the people

got back in on the other side. I was pleased to see the large number of trucks

heading north with supplies: bottles of drinking water, rolls of plastic so

people could get out of the rain, food.

We crossed six of them on our way down. It was like road construction

anywhere: you sat and waited while a long line of cars and mostly trucks slowly

passed over the bridge, guided by a man giving hand signals so you didn’t run

off the tracks. There were buses of people who got off and walked across the

bridge to the other side so the bus could go across unloaded, then the people

got back in on the other side. I was pleased to see the large number of trucks

heading north with supplies: bottles of drinking water, rolls of plastic so

people could get out of the rain, food. Back Lolli's homepage

Back Lolli's homepage